Honeycomb and Terrace Housing

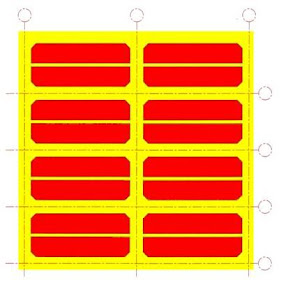

Conventional row housing and the linear approach to planning.

Dwellings can be arranged on individual plots of land as detached units or linked to each other. Whether detached or linked, they line up along streets to form row housing. In a row house, owners of individual plots of landed property maintain sole occupancy rights. Rectilinear grids have been used as the fundamental tool for subdividing land, where linear roads provide access to individually owned plots of land. Roads and gridlines may be distorted by design or necessity but they retain their linear nature.

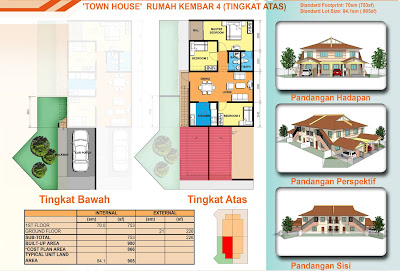

Terrace housing

Terrace housing has long been considered the densest form of landed property development possible. Indeed, of all the types of housing in Malaysia, it is the terrace house that predominates. The typical lot varies from 16’ x 50’ to 24’ x 100’, but the most common lots now are 20’ x 65’ and 22’ x 70’. The ubiquitous terrace house plan has been designed and re-designed many times but always within the same restrictive framework without much scope for innovation.

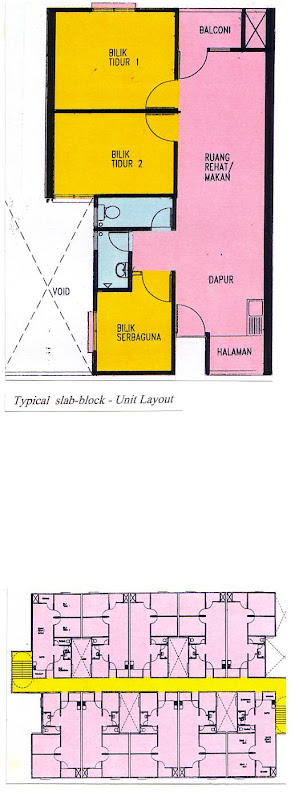

The ubiquitous terrace house

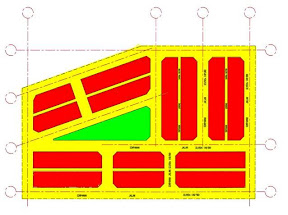

The housing layout has also become stereotyped. In the typical estate, the terrace houses are lined up along grid-lines with 40’ service roads in front and much narrower back lanes and side lanes. Communal areas for schools, civic and religious buildings, as well as open areas for children’s playgrounds and parks, are also provided. Despite the infrastructure provided, it can be said that the design of many housing estates does not really meet the practical needs of the average resident. Apart from the aesthetic boredom of rows and rows of houses, among the drawbacks of the terrace house layout is the lack of public security and any genuine sense of community . With the rising price of land in urban areas, many people are resigned to apartments. The terrace house, for all its drawbacks, has been elevated to the status of a dream-home.

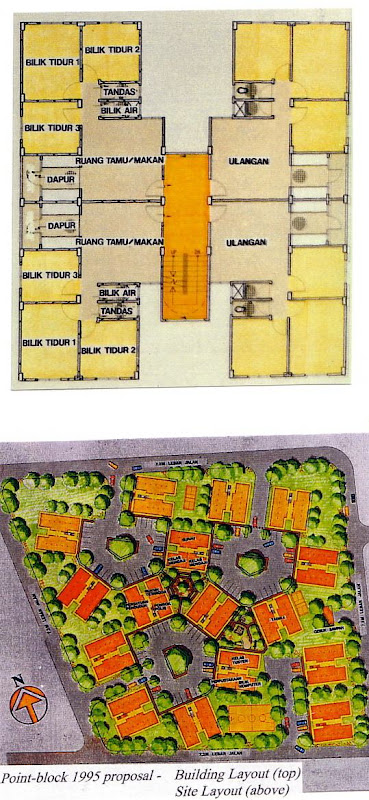

Honeycomb Housing

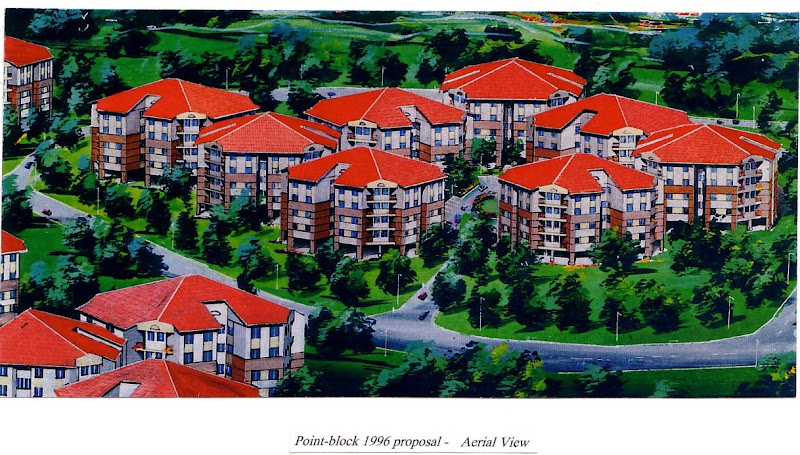

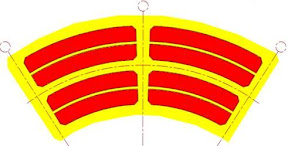

In “Honeycomb Housing”, instead of rows of terrace houses, we are proposing that every house is in a cul-de-sac with a garden in the middle, where giant shady trees will be planted. The courtyard in the middle of the houses is not just a street for transit: it is a place safe enough from speeding cars and criminals, for even pre-schoolers to play on.

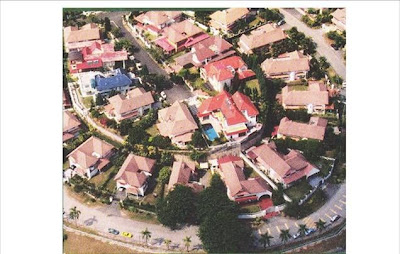

Of course houses in cul-de-sacs are very much sought after in countries like the US and Australia. The ‘horse-shoe layout’ of high-cost detached houses in Subang Jaya has been heralded as an innovative design that has sadly not been repeated elsewhere.

Source - Sime Uep Bhd advertisement

What we propose here is suitable not only for high-cost houses but can even be applied to medium cost and low-medium cost housing - even to low-cost housing. In the “Honeycomb cul-de-sac” we add a central green area as open space instead of just tarmac. This cul-de-sac, were it to be built with detached houses, and located in the Klang Valley would probably cost RM 1 million or more. They would typically have a built-up area of 4000sf, on land of about 6000sf. However, instead of detached single family homes around the cul-de-sac, we can divide the buildings into two houses such that each home faces a different cul-de-sac. In this case, each unit would only have 2000sf built-up area, on 3000sf of land. We can also partition the buildings into three, four or six so that a pair of houses faces each cul-de-sac. As we partition each building into more units, we are reducing the size of built-up area and land area for each unit. And we are increasing the number density of the development. Indeed in the sextuplex version, each house could be has a built-up area of less than 700sf and land area, 1000sf. This is already equivalent to the size of the low-cost terrace house of lot size 18’x 55’. However, take note that as we reduce the size and affordability of the housing units, we are in no way reducing the quality of the external environment found in the cul-de-sac!

Each building block can be partitioned into two, three, four or six units.

Cul-de-sac with a garden in the middle

Detached houses in this cul-de-sac, if built in the Klang valley would cost more than RM 1 million each.

Our aim is to recreate the best elements of kampong and small-town life: where children can play outside our homes with friends without fear from crime and traffic, in a community where people know and talk to each other. We are trying to create a more suitable environment for the “kampong boy of the future” – something better than our existing terrace houses. And honeycomb housing can deliver all the benefits of the cul-de-sac housing environment.

A discussion of the benefits to residents and homeowners can be found in “Honeycomb Housing and Tessellation Planning”; Planning Malaysia, Journal of the Malaysian Institute of Planners (2005) III, 71-98, Kuala Lumpur. But will the cost of land and infrastructure be higher than that of densely packed terrace housing?

Something better than our existing terrace houses